Human Rights Advocate

Above all Leonard Feather was a jazz lover, and he worked his entire life to offset anything that acted to impede originality and inspiration of the art. To this end he was a champion of equal rights. He knew that talent was not confined to any race or gender. He battled others when they refused to accept new revelations in jazz and continually chafed against limits imposed by the music business. Not believing that jazz was only a western phenomenon, he traveled extensively and helped organize concerts around the world. Everywhere he went he would listen to local groups with a knowing ear and an open mind. He worked for many years on many fronts in order to add to the splendor of the music he loved.

There were some that did not have the same attitude. Music, like all things, has conservatives that are rigid about their preferences and beliefs and do not want it to change. Leonard Feather was innovative, very accepting of new sounds, and pushed the envelope in the evolution of jazz. In 1933 he sent a letter to the editor of Melody Maker asking why no jazz had been recorded in waltz or ¾ time. The editor responded by saying “Asking for jazz in ¾ time is like asking for a red piece of green chalk”1. Unperturbed, he continued thinking about the waltz time jazz. Suggesting the idea to Benny Carter they promptly recorded ‘Waltzing the Blues’. The release caused quite a stir and much controversy. Eventually Feather was proven right and the new jazz variation was accepted, although it was almost two decades before waltz time jazz would not be seen as peculiar. Another evolution of jazz embraced and promoted by Leonard Feather was bebop. There had been a war of words going on for years about what was and what was not considered to be jazz. The Esquire jazz polls heightened this debate and raised the ire of the jazz traditionalists, also known as the Moldy Figs. When some musicians began playing a different form of jazz characterized by fast tempos and based on a harmonic structure (bebop), it was summarily denounced by many as not being jazz at all. Leonard’s book entitled Inside Bebop helped put the movement in perspective and helped its eventual acceptance. Still the change came about slowly. After convincing RCA to record some bebop, Feather suggested that the name of the album should be Bebop. Even after they had already agreed to distribute the music they refused to use the name and went with New 52nd Street Jazz instead. The new style was eventually accepted and Leonard made some enemies in the process. To make sure his work would get a fair review he had to resort to using pseudonyms, including using his friend Billy Moore’s name in place of his own.

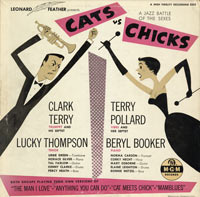

Gender inequality as a detriment to jazz creativity was challenged by Leonard Feather. Female singers had been more or less accepted from the beginning, as is shown by the success of Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, and Dinah Washington. However, attitudes held by producers and often the male musicians prevented them from participating in any other way. Feather first met Una Mae Carlisle in 1937 and was instantly impressed by her piano skills as well as her voice. She was a devoted fan of Fats Waller and played in his tradition. It was Una Mae who inspired Leonard to conceive of the blindfold test. In his first article about her in Melody Maker he wrote, “How would you like to submit to a blindfold test, listen to a typical Fats Waller song, then when the bandage was removed find that seated at the keyboard, instead of the 200 pounds of brown skinned masculinity you expected, was a light, slim, smiling girl?”2. Feather was determined to dispel the notion that women lacked the physical equipment and poise to play the instruments. His first attempt in recording an all female band called The Hip Chicks met limited success. The later album Girls in Jazz went much more smoothly. It was an all female recording featuring the Beryl Booker Trio, the Vivian Garry Quintet, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, and a band put together special for the recording consisting of Mary Lou Williams, Mary Osborne, June Rotenberg, L’Ana Hyams, and Rose Gottesman. In 1954 he brought many of them back to play on Cats vs. Chicks. Although none of the experiments did well commercially, they were musically sound, quality recordings that proved talent was not restricted to a single gender.

The gravest threat to the creativity and vitality of jazz and the one Leonard Feather worked most intensely to undo was racism. He worked his entire adult life for equal rights and racial equality. This feeling began during his first trip to the U.S. Having grown up in London he was completely unprepared for the degree of racism and segregation he witnessed. Even as Feather and others worked to get jazz out more into the main stream, it was a slow process to show that blacks were a major source of talent in jazz music. With that in mind he worked tirelessly to educate and promote jazz talent, regardless of what the artist happened to look like. He also participated in community programs and eventually joined the NAACP, becoming vice president of the Hollywood-Beverly Hills chapter in 1963.

1 The Jazz Years: Earwitness to an Era pp. 127

2 The Jazz Years: Earwitness to an Era pp. 146

References

- Feather, Leonard G. The Jazz Years: Earwitness to an Era. New York: Da Capo Press. 1987.

- Kernfeld, Barry, ed. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. St. Martin’s Press. 1994.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Grove’s Dictionaries, 3 Sub edition. 1998.

- Nytimes.com